Text networks allow you to trace the circulation of meaning within a text.

A text network analysis proceeds in the following way: a text is copied into a .txt file; it is imported into some analytic tool (I use Auto Map) in order to remove stop words and to lightly stem the text; then, using the same tool, the text—which has now been expunged of all but significant content words—is run through an algorithm that treats the content words like a network and creates a co-reference list in .csv format. What words are connected to what other words, and how often? The .csv file is then opened in a network analysis tool (I use Gephi) in order to visualize these semantic connections. Each word is visualized as a node in the network, and words that appear next to each other—within a certain word gap—appear as edges. (I used a 3-word gap below.)

The most interesting network visualization, in my opinion, shows nodes with the highest levels of Betweenness Centrality, which measures whether or not a node is connected to other nodes that themselves have many connections; a node with high betweenness centrality will in essence be an important ‘passageway’ between communities within the network. (Here’s an excellent visual description of the concepts.)

In a text network, a word with high degree centrality is a word used in connection with myriad other words. This simply tells you that a word is used frequently in a text and in a variety of contexts (it will more or less be a productive creator of bigrams). However, a word with high betweenness centrality is a word used frequently and in conjunction with other words that also connect to other words to form community clusters. This tells you that a word is not only used frequently and not only in many contexts but also that it is used in connection with words that also do a lot of semantic work in the text. A word with high betweenness centrality is a word through which many meanings in a text circulate.

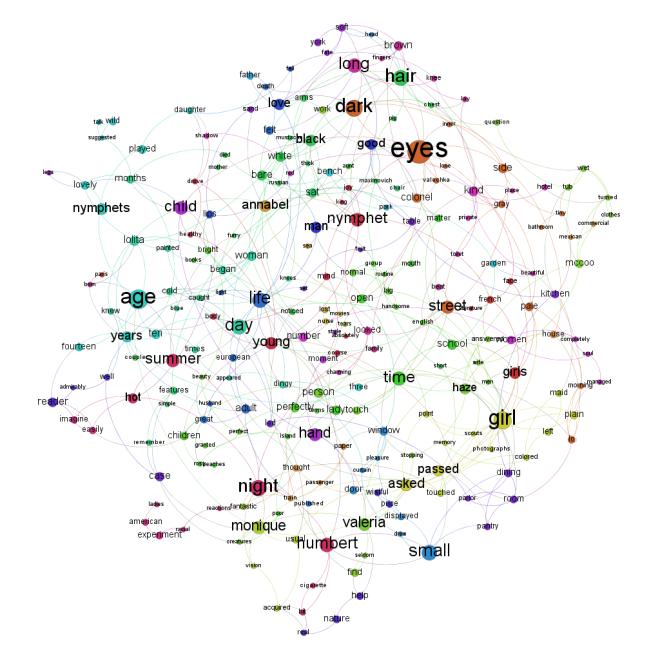

Using Auto Map and Gephi, and following a methodology similar to the one described here, I created a network of all the lexical connections within the first 10 chapters of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. (View the upcoming videos in full screen; otherwise, you can’t see the nodes I’m talking about.) The results here show which words possess the highest betweenness centrality. The more betweenness centrality, the larger the node.

The results also allow us to trace all the possible connections from one word to any other word, both within individual meaning clusters and through terms with a high level of betweenness centrality. For example, the terms ‘girl’ and ‘night’ have a relatively high betweenness centrality, and they are both connected to one another through the word ‘touched’, which itself is not connected to very many clusters and thus has a low betweenness centrality.

night –> touched –> girl

(Lots of pervy pathways of meaning in Lolita.)

Visualizing all the connections in this textual network is messy. Nabakov was a master stylist, not one to use the same words too often, and certainly not in the same sentence or in the same connective pattern. The average path length in the text is 7.95. Average path length measures how many steps you need to take on average to connect two randomly selected nodes. The lower the average path length, the more connected the text. At 7.95, the first 10 chapters in Lolita are not very connected; there are 221 separate meaning clusters. Here’s the messy initial network . . .

Using Gephi’s degree range tool, I hid the most disconnected nodes, thereby ‘cleaning’ the visualization of all but the most prominent clusters and connections.

With this cleaner network, I could see a few distinct clusters, as well as those terms with high degrees of betweenness centrality, the words that act as conduits between different words and meaning clusters. They were what you’d expected: meaning in Lolita circulates through the favorite words of an enamored pederast. Nymphet, night, girl, age, eyes, hair . . .

More interesting than the overall network, however, were the various paths I found between different terms. In general, fewer than 3 paths of separation in a social network = a possible cross-influence between two nodes. In our text network, two words separated by 3 paths or fewer = a possible, latent relationship between the words, perhaps even a relationship that can be expressed in terms of influence.

For example, ‘nymphet’ led backward to ‘annabel’, which had a direct path to ‘lolita’ in one direction and to ‘death’ in the other direction.

Remember, this textual network only represents the first 10 chapters of the novel (I didn’t include the fake preface). And yet, already built into this network of lexemes from early in the novel is a clue to Humbert’s eventual demise, a great example of the intimate connection between form and function, style and plot.

Another interesting pathway was the path between ‘life’ and ‘death’. Actually, there were two pathways, one leading through ‘felt’ and another leading, oddly enough, through ‘love’ and then ‘father’.

The ‘father’, ‘love’, ‘death’ triangle is quite interesting . . . and, of course, ‘death’ leads back through ‘felt’ to ‘annabel’, the first nymphet in Humbert’s life.

Finally, two important terms in the network are quite disconnected: ‘nymphet’ and ‘girl’. Which is exactly what we should expect. Humbert goes to great lengths to separate the one from the other, and textually, it’s difficult to trace a lexemic path from one to the other. (note: at the end of this video, I highlight the word ‘fruit’, which is only connected to ‘table’ and ‘set’. Nabokov apparently declines to use any sort of forbidden fruit metaphor during the first ten chapters of the novel; ‘fruit’ never connects to the pervy words or meaning clusters.)

Even this short analysis has given me some interesting things to discuss if I were actually writing a dissertation on Lolita. The meaning circulation of ‘lolita’, ‘annabel’, and ‘death’ through the conduit ‘nymphet’ would be worth analyzing in more detail, especially considering that this circulation occurs so early in the novel.

Pingback: Text networks, part two: Co-occurrence networks | Gods, Graves and Graphs

Pingback: Text Network and Corpus Analysis of the Unabomber Manifesto « Techna Verba Scripta

Pingback: Text network analysis 2: meaning circulation in Lolita « Techna Verba Scripta