Part III: Do linguistic structures replicate?

On the Phylogenetic Networks blog, David Morrison has posted an excellent essay regarding the (as he sees it) false analogy between languages and genes. He suggests that a more apt metaphor would be that of languages/phenotypes. He was kind enough to send me an early draft of the post. Reading it was precisely what inspired me to write a few posts of my own on this subject.

Re-reading the essay, I find myself agreeing with its point once again. If we want to find a connection between linguistic and biological evolution, we should probably take a morphological, developmental, typographic approach—in short, a phenotypic approach. Phenotypes are the observable traits of an organism, the expressions of genotypes (or, more accurately, the expressions of genotypes and environmental pressures). So, phenotypes clearly offer a more grounded and potentially productive linguistic analogy than genotypes because a language is a composite of observable traits—from the phonetic level to the semantic level. A language/genes metaphor is askew; it confuses the replicators of hereditary information with the observable expression of that information.

If found to be productive, will the language/phenotype metaphor be as suggestive as the language/genes metaphor in the debate over language origins? I’m not sure. I’m inclined to say yes—pointing still toward an essentially biological view of language—because a productive language/phenotype analogy would also suggest that languages evolve in a way comparable to physical structures. But I’ll leave that question aside for now. In this post (and perhaps the next one), I still want to play devil’s advocate and entertain the possibility of a productive language/genes metaphor.

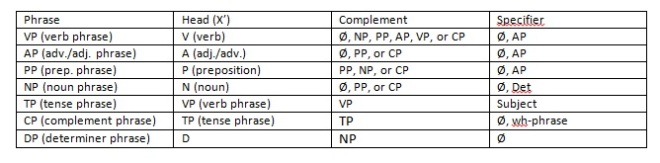

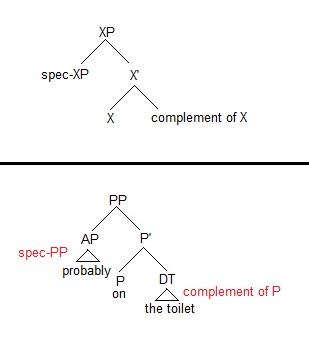

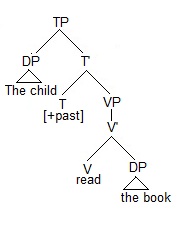

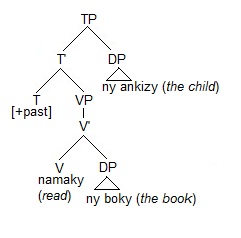

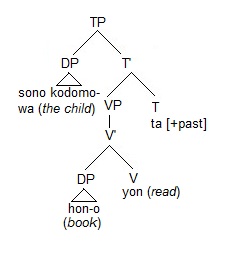

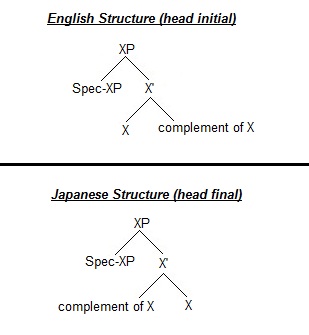

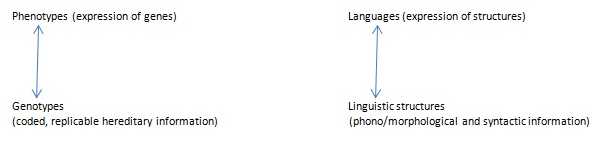

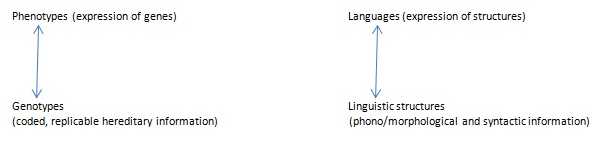

Clearly, the only way to do this is by assuming the veracity of Chomsky’s universal grammar (UG) and his principles and parameters approach. Assuming the other major linguistic theory—Halliday’s systemic functional grammar—the metaphor doesn’t work at all. It is not too misleading, however, in a Chomskyan framework, to view the phonology, morphology, and syntax of a language in a ‘genetic’ way because this framework assumes that languages are built on underlying structures that could be said to replicate themselves, in that these structures are expressed and understood by humans as language. One can view the relationship, without stretching things too much, as a two-tiered organization:

The language/structure distinction, in generative linguistics, is not as clear or even as important as the phenotype/genotype distinction in biology. But, again, we assume that languages are made possible by their underlying structures, and so it’s not entirely unfair to differentiate them for purposes of exploring this metaphor.

Do linguistic structures replicate themselves? In a sense, yes. In both first and second language acquisition research, evidence suggests that syntactic structures develop gradually. (We typically speak of grammars being ‘acquired,’ but the word denotes a structural development in the mind.) Of course, the development doesn’t begin with anything like sexual (2 parents to offspring) or even asexual (1 parent to offspring) reproduction. During first language acquisition, linguistic structures develop in the mind of a child over the course of about 2-5 years, and we might say the ‘parents’ of this linguistic development are anyone and everyone who communicates linguistically with the child, anyone who passes on structural linguistic information in the form of verbal interaction.

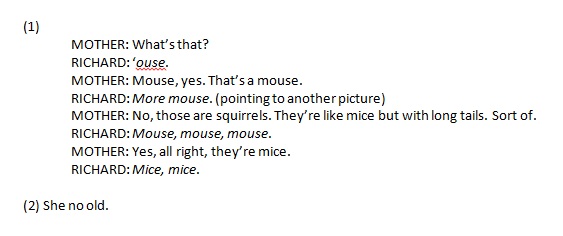

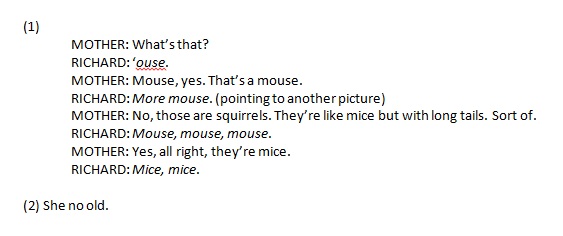

Take the following examples. (Examples come from Hawkins’ Second Language Syntax and Clark’s First Language Acquisition.) The first comes from an interaction between a 2 year old and his mother; the second comes from a second-language learner of English.

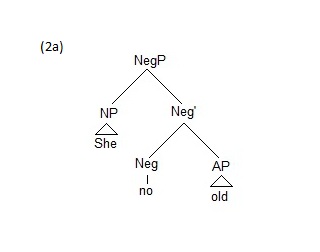

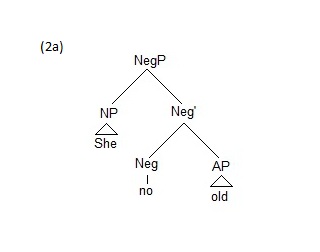

Regardless of language, children and adults first develop lexical categories—nouns, verbs, and adjectives. In (1), the child is acquiring the lexeme mouse and is in the beginning stages of acquiring its plural form, mice. In (2), the adult has acquired basic English negation. At these early stages of development, the language has not “replicated” itself completely. The structures underlying them are unspecified.

Regardless of language, children and adults first develop lexical categories—nouns, verbs, and adjectives. In (1), the child is acquiring the lexeme mouse and is in the beginning stages of acquiring its plural form, mice. In (2), the adult has acquired basic English negation. At these early stages of development, the language has not “replicated” itself completely. The structures underlying them are unspecified.

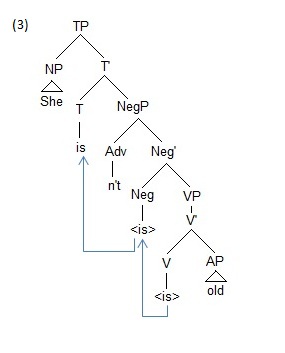

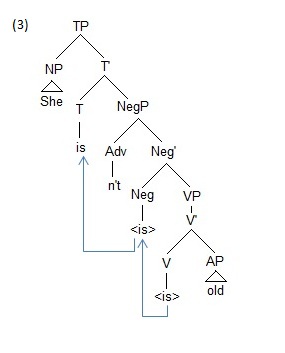

Only with time do the structures become specified: as more information is developed in the new speaker’s mind, the structures become more robust and slowly begin to replicate the fully functional language. For example, compare (2a) with (3) below, She isn’t old. (3) represents a fully developed—a fully specified— inflectional structure. The speaker is no longer working with a NegP and just attaching lexical items to it, as in (2a), She no old; instead, he has developed the category Tense, in conjunction with the ability to inflect and transform verbs. In short, the difference between (2a) and (3) is the difference between a language in the process of replication and a language that has been fully replicated in a speaker’s mind.

Only with time do the structures become specified: as more information is developed in the new speaker’s mind, the structures become more robust and slowly begin to replicate the fully functional language. For example, compare (2a) with (3) below, She isn’t old. (3) represents a fully developed—a fully specified— inflectional structure. The speaker is no longer working with a NegP and just attaching lexical items to it, as in (2a), She no old; instead, he has developed the category Tense, in conjunction with the ability to inflect and transform verbs. In short, the difference between (2a) and (3) is the difference between a language in the process of replication and a language that has been fully replicated in a speaker’s mind.

The lexicon of a language contains its lexical categories, individual words with specific conceptual content. Lexicons vary from language to language—dog, der Hund, el perro. Lexical items are often the first things to develop during first or second language acquisition. The lexicon interacts with the language’s morphology to create richer semantic meaning—add –s to pluralize in English, add –en to pluralize in German; add ed to make an English verb past tense. Morphology develops gradually along with a language’s syntax, which connects all these pieces together to form coherent utterances, i.e., sentences.

The lexicon of a language contains its lexical categories, individual words with specific conceptual content. Lexicons vary from language to language—dog, der Hund, el perro. Lexical items are often the first things to develop during first or second language acquisition. The lexicon interacts with the language’s morphology to create richer semantic meaning—add –s to pluralize in English, add –en to pluralize in German; add ed to make an English verb past tense. Morphology develops gradually along with a language’s syntax, which connects all these pieces together to form coherent utterances, i.e., sentences.

A lot of information resides in any language; it is acquired piece by piece, starting with simple words and ending with fully formed syntax. The information resides in the minds of advanced speakers, and is transferred to new speakers through verbal interaction. Every time you speak with a child or non-native speaker, you are, in a sense, pollenating their mind with linguistic information which will eventually develop into a fully structured and specified language.

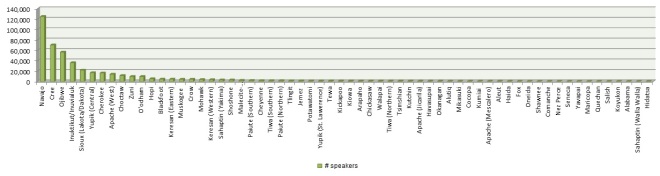

If languages do replicate in a way broadly similar to genes, then we would expect linguistic structures, like genes, to have some kind of uniform replication process. And, in many instances, we do find that linguistic structures replicate, or develop, along similar lines across different languages. (Obviously, most studies of language acquisition have been carried out with the world’s major Romance, Germanic, and Sino languages, so we don’t have anything like a complete picture of how all the world’s languages develop, but the evidence we do have suggests an organized process.)

For example, as discussed in Hawkins, several studies have shown that English verb phrases and noun phrases develop in a similar fashion across speakers, starting with bare VPs and NPs (unspecified lexical categories that simply attach to other lexical categories), moving through comparable levels of specification (e.g., the subsequent acquisition of definite article the and copula be, both of which are the ‘least specified’ specifications*), and ending with third-person singular –s and possessive –‘s.

*The and copula be are not highly specified because both select for just about anything they want. The can select a singular noun (the girl) or a plural noun (the girls) regardless of the noun’s initial phoneme; in contrast, a can only select a singular noun that begins with a vowel, so the develops before a. Likewise, copula be selects for a noun (is the man), an adjective (is happy), or a preposition (is under the table); in contrast, auxiliary be only selects for a verb ending in –ing (is running), so copula be develops before auxiliary be.

*The and copula be are not highly specified because both select for just about anything they want. The can select a singular noun (the girl) or a plural noun (the girls) regardless of the noun’s initial phoneme; in contrast, a can only select a singular noun that begins with a vowel, so the develops before a. Likewise, copula be selects for a noun (is the man), an adjective (is happy), or a preposition (is under the table); in contrast, auxiliary be only selects for a verb ending in –ing (is running), so copula be develops before auxiliary be.

More in the next post . . . I’ll end by noting that I’m only partially convinced by my own argument here about the replication of linguistic structures. As I said at the beginning, I’m more convinced that a language/phenotype analogy is more appropriate.