1

Are there any corpora that purposefully avoid “diachronicity”? There are corpora that possess no meta-data about publication dates and whose texts are therefore organized by some other scheme—for example, the IMDB movie review corpus, which is organized according to positive/negative polarity; its texts, as far as I know, are not arranged chronologically or coded for time in any way. And there are cases where time-related data are not available, easily or at all. But have any corpora been compiled with dates—the time element—purposefully elided? Is time ever left out of a corpus because that information might be considered “noise” to researchers?

Maybe in rare situations. But for most corpora whose texts span any length of time greater than a year, the texts are, if possible, arranged chronologically or somehow tagged with date information. In this universe, time flows in one direction, so assembling hundreds or thousands of texts with meta-data related to their dates of publication means the resulting corpus will possess an inherent diachronicity whether we want it to or not. We can re-arrange the corpus for machine-learning purposes, but the “time stamp” is always there, ready to be explored. Who wouldn’t want to explore it?

If we have a lot of texts—any data, really—that span a great length of time, and if we look at features in those data across the time span, what do we end up studying? In nearly all cases, we end up studying patterns of formal change and transformation across spans of time. The “evolution” metaphor suggests itself immediately. Be honest, now, you were thinking about it the minute you compiled the corpus.

One can, of course, use “evolution” as a general synonym for change. This is probably the case for Thomas Miller’s The Evolution of College English and for many other studies whose data extend only to a limited number of representative sources. However, when it comes to distant readings, the word becomes much more tempting. The trees of Moretti’s Graphs, Maps, Trees are explicitly evolutionary:

For Darwin, ‘divergence of character’ interacts throughout history with ‘natural selection and extinction’: as variations grow apart from each other, selection intervenes, allowing only a few to survive. In a seminar a few years ago, I addressed the analogous problem of literary survival, using as a test case the early stages of British detective fiction . . . (70-71)

The same book ends with an afterword by geneticist Alberto Piazza (who worked with Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza on The History and Geography of Human Genes). Piazza writes:

[Moretti’s writings] struck me by their ambition to tell the ‘stories’ of literary structures, or the evolution over time and space of cultural traits considered not in their singularity, but their complexity. An evolution, in other words, ‘viewed from afar’, analogous at least in certain respects to that which I have taught and practiced in my study of genetics. (95)

Analogous at least in certain respects . . . For Moretti and Piazza, literary evolution is not just a synonym for change in literature. Biological evolution becomes a guiding metaphor (not perfect, by any means) for the processes of formal change analyzed by Moretti. Piazza continues:

The student of biological evolution is especially interested in the root of a [phylogenetic] tree (the time it originated). . . . The student of literary evolution, on the other hand, is interested not so much in the root of the tree (because it is situated in a known historical epoch) as in its trajectory, or metamorphoses. This is an interest much closer to the study of the evolution of a gene, the particular nature of whose mutations, and the filter operated by natural selection, one wants to understand . . . (112-113)

Obviously, for Piazza, Moretti’s study of changes to and migrations of literary form in time and space evokes the processes and mechanisms of biological evolution—there’s not a one-to-one correspondence, of course, and Piazza points this out at length, but the similarities are evocative enough that he, a population geneticist, felt confident publishing his thoughts on the subject.

In Distant Reading, Moretti has more recently acknowledged that the intense data collection and quantitative analysis that has marked work at Stanford’s Literary Lab must at some point heed “the need for a theoretical framework” (122). Regarding that framework, he writes:

The results of the [quantitative] exploration are finally beginning to settle, and the un-theoretical interlude is ending; in fact, a desire for a general theory of the new literary archive is slowly emerging in the world of digital humanities. It is on this new empirical terrain that the next encounter of evolutionary theory and historical materialism is likely to take place. (122)

In Macroanalysis, Matthew Jockers also acknowledges (and resists) the temptation to initiate an encounter between evolutionary theory and the quantitative, diachronic data compiled in his book:

. . . the presence of recurring themes and recurring habits of style inevitably leads us to ask the more difficult questions about influence and about whether these are links in a systematic chain or just arbitrary, coincidental anomalies in a disorganized and chaotic world of authorial creativity, intertextuality, and bidirectional dialogics . . .

“Evolution” leaps to mind as a possible explanation. Information and ideas do behave in a ways that seem evolutionary. Nevertheless, I prefer to avoid the word evolution: books are not organisms; they do not breed. The metaphor for this process breaks down quickly, and so I do better to insert myself into the safer, though perhaps more complex, tradition of literary “influence” . . . (155)

And in the last chapter to Why Literary Periods Mattered, Ted Underwood does not mention evolution at all but there is clearly an evolutionary connotation to the terms he uses to describe digital humanities’ influence on literary scholars’ conception of history:

. . . digital and quantitative methods are a valuable addition to literary study . . . because their ability to represent gradual, macroscopic change brings a healthy theoretical diversity to literary historicism . . .

. . . we need to let quantitative methods do what they do best: map broad patterns and trace gradients of change. (159, 170)

Underwood also discusses “trac[ing] processes of change” (160) and “causal continuity” (161). The entire thrust of Underwood’s argument, in fact, is that distant or quantitative readings of literature will force scholars to stop reading literary history as a series of discrete periods or sharp cultural “turns” and to view it instead as a process of gradual change in response to extra-literary forces—“Romanticism” didn’t just become “Naturalism” any more than homo erectus one decade decided to become homo sapiens.

Tracing processes of gradual, macroscopic change . . . if that doesn’t invoke evolutionary theory, I don’t know what does. Underwood doesn’t even need to use the word.

Moretti, Jockers, and Underwood are three big names in digital humanities who have recognized, either explicitly or implicitly, that distant reading puts us face to face with cultural transformation on a large, diachronic scale. Anyone working with DH methods has likely recognized the same thing. Like I said, be honest: you were already thinking about this before you learned to topic model or use the NLTK.

2

Human culture changes—its artifacts, its forms. This is not up for debate. Even if we think human history is a series of variations on a theme, the mutability of cultural form remains undeniable, even more undeniable than the mutability of biological form. Distant reading, done cautiously, gives us a macro-scale, quantitative view of that change, a view simply not possible to achieve at the scale of individual texts or artifacts. Given the fact of cultural transformation, then, and DH’s potential to visualize it, to quantify aspects of it, one of two positions must be taken.

1. The diachronic patterns we discover in our distant readings are, to use Jockers’ words, “just arbitrary, coincidental anomalies in a disorganized and chaotic world of authorial creativity, intertextuality, and bidirectional dialogics.” Theorizing the patterns is a fool’s errand.

2. The diachronic patterns we discover are not arbitrary or random. Theorizing the patterns is a worthwhile activity.

Either we believe that there are processes guiding cultural change (or, at least, that it’s worthwhile to discover whether or not there are such processes) or we assume a priori that no such processes exist. (A third position, I suppose, is to believe that such processes exist but we can never know them because they are too complex.) We can all decide differently. But those who adopt the first position should kindly leave the others to their work. In my view, certain criticisms of distant reading amount to an admonition that “What you’re trying to do just can’t be done.” We’ll see.

3

When we decide to theorize data from distant readings, what are we theorizing? Moretti, Jockers, and Underwood each provide a similar answer: we are theorizing changes to a cultural form over time and, in some instances, space. Certain questions present themselves immediately: Are the changes novel and divergent, or are they repeating and reticulating? Is the change continuous and gradual, or are there moments of punctuated equilibrium? How do we determine causation? Are purely internal mechanisms at work, or also external dynamics? A complex interplay of both internal mechanisms and external dynamics? How do we reduce data further or add layers of them to untangle the vectors of causation?

To me, all of this sounds purely evolutionary. Even talking about gradual vs. quick change is a discussion taken right out of Darwinian theory.

But we needn’t adopt the metaphor explicitly if we are troubled that it breaks down at certain points. Alex Reid writes:

Matthew Jockers remarks following his own digital-humanistic investigation, “Evolution is the word I am drawn to, and it is a word that I must ultimately eschew. Although my little corpus appears to behave in an evolutionary manner, surely it cannot be as flawlessly rule bound and elegant as evolution” (171). As he notes elsewhere, evolution is a limited metaphor for literary production because “books are not organisms; they do not breed.” He turns instead to the more familiar concept of “influence” . . . Certainly there is no reason to expect that books would “breed” in the same way biological organisms do (even though those organisms reproduce via a rich variety of means). [However], if literary production were imagined to be undertaken through a network of compositional and cognitive agents, then such productions would not be limited to the capacity of a human to be influenced. Jockers may be right that “evolution” is not the most felicitous term, primarily because of its connection to biological reproduction, but an evolutionary-type process, a process as “natural” as it is “cultural,” as “nonhuman” as it is “human,” may exist.

An “evolutionary-type” process of culture is what we’re after, one that is not necessarily reliant on human agency alone. Will it end up being “flawlessly rule bound and elegant as evolution”? First, I think Jockers seriously over-estimates the “flawless” nature of evolutionary theory and population genetics. If the theory of evolution is so flawless and elegant, and all the science settled, what do biologists and geneticists do all day? Here’s a recent statement from the NSF:

Understanding the tree of life has been a goal of evolutionary biologists since the time of Darwin. During the past decade, unprecedented gains in gathering and analyzing phylogenetic data have demonstrated increasingly complex genealogical patterns.

. . . . Our current knowledge of processes such as hybridization, endosymbiosis and lateral gene transfer makes clear that the evolutionary history of life on Earth cannot accurately be depicted as a single, typological, bifurcating tree.

Moretti, it turns out, needn’t worry so much about the fact that cultural evolution reticulates. And Jockers needn’t assume that biological evolution is elegantly settled stuff.

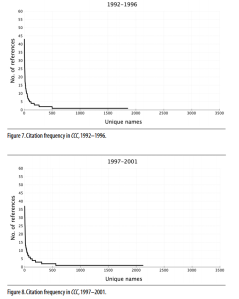

Secondly, as Reid argues, we needn’t hope to discover a system of influence and cultural change that can be reduced to equations. We probably won’t find any such thing. However, within all the textual data, we can optimistically hope to find regularities, patterns that can be used to make predictions about what might be found elsewhere, patterns that might connect without casuistic contrivance to theories from the sciences. Here’s an example, one I’ve used several times on this blog: Derek Mueller’s distant reading of the journal College Composition and Communication. Mueller used article citations as his object of analysis. When he counted and graphed a quarter century of citations in the journal, he discovered patterns that looked like this:

Actually, based on similar studies of academic citation patterns, we could have predicted that Mueller would discover this power law distribution. It turns out that academic citations—a purely cultural form, a textual artifact constructed through the practices of the academy—behave according to a statistical law that seems to affect all sorts of things, from earthquakes to word frequencies. This example makes a strong case against those who argue that cultural artifacts, constructed by human agents within their contextualized interactions, will not aggregate over time into scientifically recognizable patterns. Granted, this example comes from mathematics, not evolutionary theory, but it makes the point nicely anyway: the creations of human culture are not necessarily free from non-human processes. Is it foolish to look for the effects of these processes through distant reading?

4

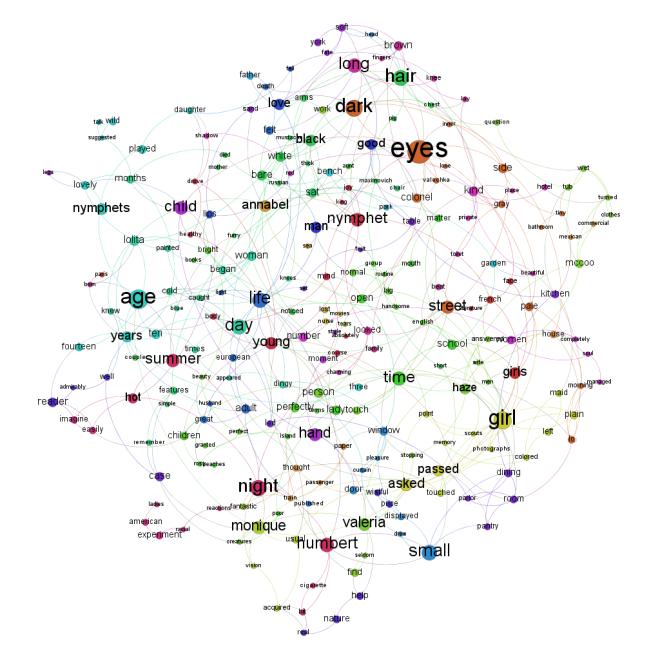

“Evolution,” “influence,” “gradualism”—whatever we call it in the digital humanities, those of us adopting it on the literary and rhetorical end have a huge advantage over those working in history: we have a well-defined, observable element, an analogue of DNA, to which we can always reduce our objects of study: words. If evolution is going to be a guiding metaphor, we need this observable element because it is through observations of its metamorphoses (in usage, frequency, etc.) that we begin to figure out the mechanisms and dynamics that actually cause or influence those metamorphoses. If we had no well-defined segment to observe and quantify, the evolutionary metaphor could be thrown right out.

To demonstrate its importance, allow me a rhetorical demonstration. First, I’ll write out Piazza’s description of biological evolution found in his afterword to Graphs, Maps, Trees. Then, I’ll reproduce the passage, substituting lexical and rhetorical terms for “genes” but leaving everything else more or less the same. Let’s see how it turns out:

Recognizing the role biological variability plays in the reconstruction of the memory of our (biological) past requires ways to visualize and elaborate data at our disposal on a geographical basis. To this end, let us consider a gene (a segment of DNA possessed of a specific, ascertainable biological function); and for each gene let us analyze its identifiable variants, or alleles. The percentage of individuals who carry a given allele may vary (very widely) from one geographical locality to another. If we can verify the presence or absence of that allele in a sufficient number of individuals living in a circumscribed and uniform geographical area, we can draw maps whose isolines will join all the points with the same proportion of alleles.

The geographical distribution of such genetic frequencies can yield indications and instruments of measurement of the greatest interest for the study of the evolutionary mechanisms that generate genetic differences between human populations. But their interpretation involves quite complex problems. When two human populations are genetically similar, the resemblance may be the result of a common historical origin, but it can also be due to their settlement in similar physical (for example, climactic) environments. Nor should we forget that styles of life and cultural attitudes of an analogous nature (for example, dietary regimes) can favour the increase or decrease to the point of extinction of certain genes.

Why do genes (and hence their frequencies) vary over time and space? They do so because the DNA sequences of which they are composed can change by accident. Such change, or mutations, occurs very rarely, and when it happens, it persists equally rarely in a given population in the long run . . . From an evolutionary point of view, the mechanism of mutation is very important because it introduces innovations . . .

. . . The evolutionary mechanism capable of chancing the genetic structure of a population most swiftly is natural selection, which favours the genetic types best adapted for survival to sexual maturity, or with a higher fertility. Natural selection, whose action is continuous over time, having to eliminate mutations that are injurious in a given habitat, is the mechanism that adapts a population to the environment that surrounds it. (100-101)

Now for the “distant reading” version:

Recognizing the role lexical variability plays in the reconstruction of the memory of our (literary and rhetorical) past requires ways to visualize and elaborate data at our disposal on the basis of cultural space (which often correlates with geography). To this end, let us consider a word (a segment of phonemes and morphemes possessed of a specific, ascertainable grammatical or semantic function); and for each word let us analyze its stylistic variants, or synonyms. The percentage of texts that carry a given stylistic variant may vary from one cultural space to another, or from one genre to the other. If we can verify the presence or absence of that variant in a sufficient number of texts produced in a circumscribed and uniform cultural space we can draw maps whose isolines will join all the points with the same proportion of stylistic variants.

The distribution of such lexical frequencies can yield indications and instruments of measurement of the greatest interest for the study of the evolutionary mechanisms that generate lexical differences between “generic populations.” But their interpretation involves quite complex problems. When two rhetorical forms or genres are lexically similar, the resemblance may be the result of a common historical origin, but it can also be due to their development in similar geographic or political environments. Nor should we forget that styles of life and cultural attitudes of an analogous nature (for example, religious dictates) can favour the increase or decrease to the point of extinction of certain lexical items or clusters of lexical items.

Why do words (and hence their frequencies and “clusterings”) vary over time and space? They do so because of stylistic innovations. Such innovation occurs very rarely, and when it happens, it persists equally rarely in a given generic population in the long run . . . From an evolutionary point of view, the mechanism of innovation is very important because it introduces new rhetorical forms . . .

. . . The evolutionary mechanism capable of changing the lexical structure of a rhetorical form or genre most swiftly is cultural selection, which favours the forms best adapted for survival to publication and circulation, or with a higher degree of influence (meaning a higher likelihood of being reproduced by others without too many changes). Cultural selection, whose action is continuous over time, having to eliminate rhetorical innovations or “mutations” that are injurious in a given cultural habitat, is the mechanism that adapts a rhetorical form to the environment that surrounds it.

Obviously, it’s not perfect. I leave it to the reader to decide its persuasive potential.

I think the biggest problem is in the handling of mutations. In biological evolution, genes mutate via chance variations during replication of their segments; these mutations can introduce innovations in an organism’s form or function. In literary evolution, however, no sharp distinction exists between a lower-scale “mutation” and the innovation it introduces. The innovation is the formal mutation. This issue arises because, in literary evolution, as in linguistic evolution, the genotype/phenotype distinction is not as obvious or strictly scaled as it is in evolutionary theory. Words are more phenotype than genotype, unless we want to get lost in an overly complex evocation of morphology and phonology.

The metaphor always breaks down somewhere, but where it works, it is, I think, highly suggestive: the idea is that we track rhetorical forms—constellations of words and their stylistic variants—across time and space, in order to see where the forms replicate and where they disappear. Attach meta-data to the texts that constitute those forms, and we will have what it takes to begin making data-driven arguments about how cultural ecology affects or does not affect cultural form.

It’s an interesting framework in which distant reading might go forward, even if explicit uses of the word “evolution” are abandoned.